In The Beginning

An account of a pioneer journey to Rhodesia in the early 1890s

by Peter Hardwicke

.

Around the circled ox-wagons life is beginning to stir. It is an early morning on the African high-veld in the year 1890 and a phenomenon unique to Africa is about to unfold. It is known as the False Dawn and heralds the arrival of a new day. As the sky lightens the people of the wagon train set about their chores. The women set the fires and start the coffee while the children pack up their belongings. The men move among the oxen and begin the long process of “in-spanning”- collecting the oxen and hitching them to the wagons. Each wagon will use 8 pairs of oxen, known as a full span. Soon all the wagons are ready and, as the smell of freshly-brewed coffee mingles with that of the campfire, the families settle down to enjoy a cup of coffee before starting the day’s trek. Around them the birds are welcoming the new day. The oxen stand contentedly chewing and waiting to begin their work. Then the light begins to fade signalling the end of the False Dawn.

Now all is silent. The birds stop their singing and all the animals stand quietly. Even the wind seems to still and the surrounding veld dissolves into the intensifying darkness. This is a time of the day when the world seems to hold its breath, as it waits for the new day. The only sound is the low murmuring of the pioneers as they discuss plans for this day.

At last a lark is heard high above them announcing that the real dawn is about to break. Coffee cups are emptied and stowed on the wagons, fires are put out and everyone prepares for a long day of walking, for there was only room on the wagons for possessions and supplies. As the pioneers take up their positions the silence is shattered by the sharp crack of the drivers’ whips and shouts of encouragement as the oxen strain to start the four-ton wagons moving. Slowly the circle is broken as the oxen follow the “voorlopers” (usually young boys who walk in front of the oxen) and the day’s trek begins.

Thus starts a day in the life of a pioneer who, in 1890, left Cape Town in South Africa and journeyed to Rhodesia. The journey covered nearly 2000 miles and took four years. My grandmother, Philipina Scheffer, as a little girl of 10, was a member of that pioneer column. I always loved to hear her talk about the journey and admired her for the endurance required to walk the entire way, but such was the spirit of the pioneer. I say she walked, but when her father wasn’t looking she would ride the horses. Because they were going to a new and unsettled country, the pioneers had to take everything they needed with them. This meant extra cattle for pulling and breeding, as well as some chickens, sheep and horses. To the children with the column fell the task of herding these animals. The pioneer column needed to stop every few days to rest the animals and give them a chance to graze, making progress so slow that they did not reach Fort Salisbury until 1894. In some places it was necessary to clear trees from the roadway so the wagons could continue. The one thing a pioneer could not afford was impatience. It was best to put their watches and calendars away and just take what the country and the weather gave them, for to do otherwise was to court disaster.

A typical day in the life of a pioneer column would start as described above. In the early stages the process of in-spanning was very stressful and time consuming. After a while each of the oxen learnt their names and their position within the span. As far as was possible, the drivers always tried to put an ox in the same place. Certain beasts were suitable to lead and others excelled at encouraging their fellow oxen from the rear position. Thus, as the journey progressed, it became necessary only to call the oxen by their names and they would amble up to their position and wait for the yoke to be lifted, at which time they would walk under it and allow themselves to be in-spanned. The wagon train would be on the move from sun-up until about noon, at which time, during the heat of the day, it would stop to rest the oxen and to have lunch. The time that the column stopped varied, as they usually tried to make sure that there was water and grass available for the oxen, which would be out-spanned and allowed to drink and graze. Around 3pm the oxen would be in-spanned again and the trek resumed until nightfall. The wagons would then be circled for the night. By circling the wagons the pioneers reduced the chance of predators carrying off any livestock or even children. Supper would be cooked and there would be some entertainment until everyone retired for the night. Some forms of entertainment would be dancing, singing or playing “jukskei”. This was the South African equivalent of horseshoes. The name is derived from the Afrikaans name for the wooden piece (the skei) that was passed through the yoke that rested on the ox’s shoulders. There were two of these on each half of the yoke, one on each side of the ox’s neck, and a piece of rawhide was attached to them, passing under the neck. The skeis would be removed from the yoke and pitched like horseshoes towards a target. The closest to the target would win. Often at this time some of the men would go hunting to supplement their larders. Some of the meat, usually venison, would be cooked and some made into biltong, which is the Afrikaans equivalent of [American] jerky. Thus preserved, the meat could be given to toddlers who were teething or carried in the pocket and snacked on to ease hunger pains without having to stop. Hunting was not an arduous task, as at that time game was plentiful and not as skittish as it is today. Often, during the migration season, the wagon train would be held up for 2 or 3 days while herds of animals passed in front of it. There are reports of a single herd of migrating springbok and ostriches taking 3 days to pass a given point.

If the terrain was friendly and the weather fair, the wagon train would travel about six miles in a day. There were, however, many days when these ideal conditions were not there. Incredible hardships had to be endured when rivers had to be crossed or hills climbed. On these days only a mile or two would be made. The technique for crossing a river, if a shallow ford could not be found, would be to cut down some trees to make a raft and then float the wagons across the river one at a time. Care had to be taken when swimming the livestock across that there were no crocodiles in the area. It would often take all day to accomplish this, so that night camp would be set up on the opposite bank from the previous night. During these crossings was just about the only time that the women, with their long dresses, and children were able to ride on the wagons, as the currents usually proved too dangerous for them. Where steep inclines were encountered, the wagons, which were capable of carrying up to four and a half tons, often proved too heavy for the normal team of oxen to manage. In these circumstances one or two teams would be detached from other wagons and each wagon would be double or triple teamed in order to get to the top of the rise. This meant that each team of oxen would make two or three trips and needed to be rested when all the wagons were finally up. Once again only a couple of miles would be covered in a day. A really bad day would follow an overnight rain, when the wagons would be faced with a steep climb up the hill which, the next morning, was like grease. On these days there was nothing to do but wait for the hill to dry. Each wagon was equipped with large wood blocks on the rear wheels. These were the brakes and were operated by a handle attached to a large turn screw. On many downhill slopes men had to walk behind the wagon ready to apply the brakes at a moment’s notice to prevent the wagon from rolling over the oxen pulling it. Sometimes six of the oxen were moved to the back of the wagon, leaving two to steer the wagon while the remaining six held it back, helping the brakes. This also, in the event of a runaway, reduced the number of casualties among the ever precious oxen.

.

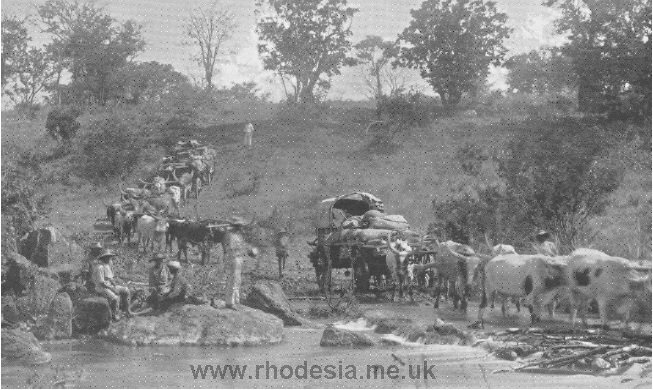

A typical scene during the days of Ox Wagon Transportation

.

These pioneers needed to be resourceful, but above all they had to be very patient. Life moved at a set pace and could not be hurried. Animals needed to be well cared for as there were very limited replacements if an ox was injured or killed. One constant danger was from the wild animals that were all around. Many predators saw the oxen, and very often the pioneers themselves, as easy prey and any animal or person who wandered too far from the wagons was in danger of being attacked. Rabies was also prevalent and rabid animals had been known to fearlessly attack the column, even in daylight. A bite by a rabid animal was an automatic death sentence, as there was no cure. Another scourge was the rapid infection of any minor scrape or cut. The pioneer women were usually well versed in herbal cures and adept at doctoring any who got hurt or became ill. Many of their recipes were handed down. My mother used these on me on many occasions. They were most effective and usually cleared things up in a couple of days.

Over the two years of the trek some wagons were lost through accidents or simply fell apart due to the stress of the journey. There were births, deaths and even a couple of marriages. However enough pioneers and supplies completed the journey to enable them to establish a thriving settler community.

My grandmother was 14 when she arrived in what was then Fort Salisbury and is today Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe.

Grandmother seldom talked about the trek from South Africa, but often told stories from her life on the farm. I always remember her telling me how she cheated death twice. “The first time” she used to say, “Was the day that the wild dogs chased a large buck into the farm yard. I tried to chase it off by shouting at it, but it charged me. As I stepped back I tripped on the hem of my dress and fell backwards. Fortunately the buck jumped over me and ran off.” She also told of how, when she was 8 months pregnant with twins, she had to ride 60 miles in a cart during the rainy season when the roads were just water and mud, and all the rivers full. This was a week before the twins were born, and then, when they were 10 days old, she made the return journey.

The second time Grandmother cheated death was in 1940 when she was in the accident that killed her husband. He was crushed, while she escaped with her arm broken in five places. In spite of this injury, she was able to do prize winning fine needlework well into her old age. It was her eyesight, and not her arm, that finally forced her to give this up.

My grandfather, Daniel Ayliff Tarr, was born near Grahamstown, South Africa, in 1862. He became a Transport Driver and owned 2 ox-wagons with which he used to transport goods from the railhead to the early settlements. In 1890 he crossed the Limpopo River from South Africa into Rhodesia for the first time, and fell in love with the country. He determined to settle there and take up farming. In order to accumulate a nest egg he continued to transport goods between Kimberly and the newly established Fort Salisbury. On one of these journeys in 1894 he fell in with a column of settlers going to Rhodesia. Among the settlers in the column was an attractive 14 year old, to whom my grandfather took a particular liking. By the time the column reached Fort Salisbury a year later they had become firm friends. Soon after this, grandfather lost all his oxen to rinderpest. (This is a type of fever which spread to Southern Africa from Europe and North Africa in the late 19th century and wiped out about eighty-five percent of the cattle. It was spread from food sources and, as the settlers discovered, buried animals remained a source of infection for many months.) When Cecil Rhodes, who was the driving force in the settlement of Rhodesia and after whom the country was named, heard of this he immediately wrote a cheque and instructed my grandfather to buy more oxen and continue to transport goods to the new settlement. At this time the wagons were the only transport capable of moving supplies from the railhead to the settlements and mines of the newly founded colony. While I was never able to talk to my grandfather about his adventures while transport driving, I was able to find some stories that will illustrate the tribulations that these intrepid pioneers faced.

During the rainy season many areas became waterlogged bogs of greasy black mud. Wagons easily became stuck in these, often sinking up to their axles in the mud. On one occasion a wagon, loaded with about three tons of general supplies for a settlement, became stuck, sinking to its axles, with the oxen up to their bellies in the mud. There was no hope of moving the wagon as the team could find no traction. There was a mine close by; less than a day’s ride. The driver set off and borrowed some corrugated iron sheeting from the mine. Returning to his wagon he unloaded it and, using the sheets as skids, moved the merchandise to higher ground. With the wagon empty, he attached a long chain to it, enabling the oxen to stand on the firmer ground and pull the wagon out of the mud. After this was accomplished the wagon was reloaded and the oxen rested for a day, while he returned the corrugated iron sheets to the mine. The result of this exercise is that only half a mile of progress was made in five days but the precious cargo was saved!

Another story also involved a wagon stuck in the mud. On this occasion the cargo was a four-ton boiler destined for a local mine. Unloading the wagon was out of the question, so additional oxen were borrowed from other wagons in the convoy and added to the span. Eventually there were five complete spans, totalling 80 oxen, attached and they were finally able to pull the wagon out. Unfortunately it slid from under the boiler, leaving it sinking into the mud. The boiler was abandoned and probably still lies there.

I should like to include, here, a brief description of the whips carried by the transport drivers. They were usually about thirty feet in length and were attached to a fifteen foot pole. With this whip the driver was able to reach the lead oxen. Good drivers seldom, if ever, struck their oxen. The whip was used to crack above the oxen to encourage them, or beside them to turn the lead pair. I used to practice with these whips when I was a young lad on the farm and admired the skill of the drivers in being able to “Flick a fly off the ear of the leading ox without touching him”.

In 1896 Daniel Ayliffe Tarr was 34 and engaged to 16 year old Philipina Sheffer. He was bringing 2 wagons loaded with much need supplies to Salisbury, on what was to be his last trip, when he was involved in an accident that, while it cost him his wagons, oxen and goods, almost certainly saved his life.

It had been raining and the ground was very slippery. On quite a few occasions he needed to double span his wagons in order to negotiate a hill. On one occasion he was going downhill and walking behind the wagon in order to slow it with the brakes when one of the wooden blocks broke and the wagon careened forward, killing many of the oxen and scattering its load as it broke up. The other people accompanying him helped to gather the scattered goods and put them on the broken wagon. My grandfather covered them with a tarp and, instructed his driver and voorloper to guard them, intending to deliver his remaining wagon load to Salisbury and then return for them. During an overnight stop with his remaining wagon about 40 miles from Salisbury he became very restless. Finally surrendering to this restlessness, at about three o’clock in the morning he in-spanned and gave instructions to his driver to bring the wagon through and then set out to walk the remaining distance alone. Waiting for him in Salisbury was his young fiancée, Philipina Scheffer. They were to be married when he arrived there and he was to give up his transport business and start farming. The goods in his wagon were the nest egg. He arrived in Salisbury the next day, having walked through the night, only to find the city under siege and all the women and children in the jail; this being the safest place for them. He was told that the local Mashona tribe had risen in rebellion. Later he discovered that his decision to leave the wagon had saved his life, as the wagon had been looted and all those with it had been killed.

After my grandparents were married, Cecil Rhodes, who had heard of my grandfather’s misfortunes, gave them a farm as a wedding present. My grandfather promptly named this farm “Philipsdale” in honour of his new bride. My mother and all of her 12 siblings were born here. My grandparents were married for 46 years and had 13 children. Seven of the children died before reaching adulthood, the oldest being Eileen, who died at age 17. The remaining 6 children all married, producing 17 grandchildren and 24 great-grandchildren. My grandfather was crushed to death in a car accident in 1940 at age 77, but my grandmother, who was born in 1880 and lived to see her world go from ox-wagons to jumbo jets, died in May 1969, 2 months before Neil Armstrong landed on the moon.

.

© Peter Hardwicke who has kindly consented to the publication on this site of the above extract from his private family book: A Most Fortunate Life

See also: How to start a new country – Pioneer Travel in early Rhodesia